What is an Original Print? A Printmaker's Guide

Updated December 2025

And Where Giclée Prints Fit In.

Introduction

If you've ever felt confused about what makes a print "original," you're not alone. Walk into any gallery or browse art online, and you'll encounter the word "print" used to describe everything from museum-quality artworks to mass-produced posters. Let me clear up the confusion and introduce you to the world of original printmaking.

The Confusion: "Print" Means Many Things

Here's the problem: the word "print" has become so broad it's almost meaningless without context. It can refer to:

Original artworks created through printmaking techniques

High-quality reproductions of paintings or drawings

Mass-produced posters run off by the thousands

Digital prints from home inkjet printers

No wonder collectors feel bewildered.

What Makes a Print "Original"?

An original print is a work of art created by an artist using printmaking techniques such as monotype, collagraph, etching, lithography, screenprinting, or relief printing. Here's what distinguishes original prints:

The artist conceives the work specifically for the printmaking medium. They're not reproducing something created in another medium—they're thinking in terms of what printmaking can uniquely accomplish.

The artist creates the matrix. This might be a carved woodblock, an etched copper plate, a lithographic stone, a silk screen, or a textured collagraph plate. The artist builds the physical element from which prints are made, or in the case of monotype, the artist ‘paints’ ink onto a smooth surface from which the print is taken. There are no permanent marks on the surface, so the image is not repeatable.

The artist is intimately involved in the printing process. They may pull the prints themselves, as I do, or work closely with a master printer, making decisions about what paper to use, ink colours and consistency, press pressure, where and how to use found materials and registration at every stage.

Each print is an artwork in its own right, not a copy of something else. Even in an edition of identical prints, each one is considered an original work of art, because each time the plate is inked up by hand by the artist or the master printer.

My Techniques: Monotype and Collagraph

In my practice, I work with these two distinctive printmaking techniques, sometimes just one or the other and sometimes in combination.

Monotype print created in layers, both reductive (wiping away ink) and additive (adding ink), and using plants as masks and to print with.

Monotype

Monotype is perhaps the most painterly of all printmaking methods. I create each image by ‘painting’ ink onto the smooth plate with rollers, brushes, and pieces of card. I also draw into the ink on a smooth plate (typically perspex or metal) using oil-based printing inks. Then I place damp paper over the inked plate and run it through a press, to transfer the image.

What makes monotypes special—and sometimes confusing for collectors—is that each one is unique. The plate holds no permanent image; once I pull the print, most of the ink transfers to the paper. Occasionally, there is enough residual ink to take a fainter second impression. This is called the "ghost" image, which I might add to with further layers, or not, but each impression is an original one-of-a-kind print.

Are monotypes "original prints" if they're unique rather than multiple? Definitely! They use printmaking processes and materials, and the indirect transfer through the press creates qualities impossible to achieve through direct painting or drawing (or AI). There is always an element of serendipity in how ink transfers, the way pressure affects the image, and the characteristic printing inks create—these are distinctly printmaking qualities. That part is completely out of my control and the most exciting part of the process!

Collagraph

Collagraph is a more textured, relief-based technique. I build up printing plates by glueing various materials to a rigid surface—textured papers, fabrics, carborundum, modelling paste, found objects—creating a collaged plate with varied heights and textures.

Once the plate is sealed, I apply the ink with a combination of tools, card, brushes, and rollers. The ink has to be worked into the paket to get it into the grooves of texture before the excess ink is wiped off. Once the plate is inked, I place damp paper over it and run it through a press under significant pressure. The result is a print with rich, embossed textures—you can see and feel the dimensionality of the plate pressed into the paper.

Unlike monotypes, collagraph plates can print multiple impressions, making them suitable for limited editions. The plate does wear down over time, which naturally limits how many prints can be pulled, but I typically create editions of up to 20 prints from a single collagraph plate.

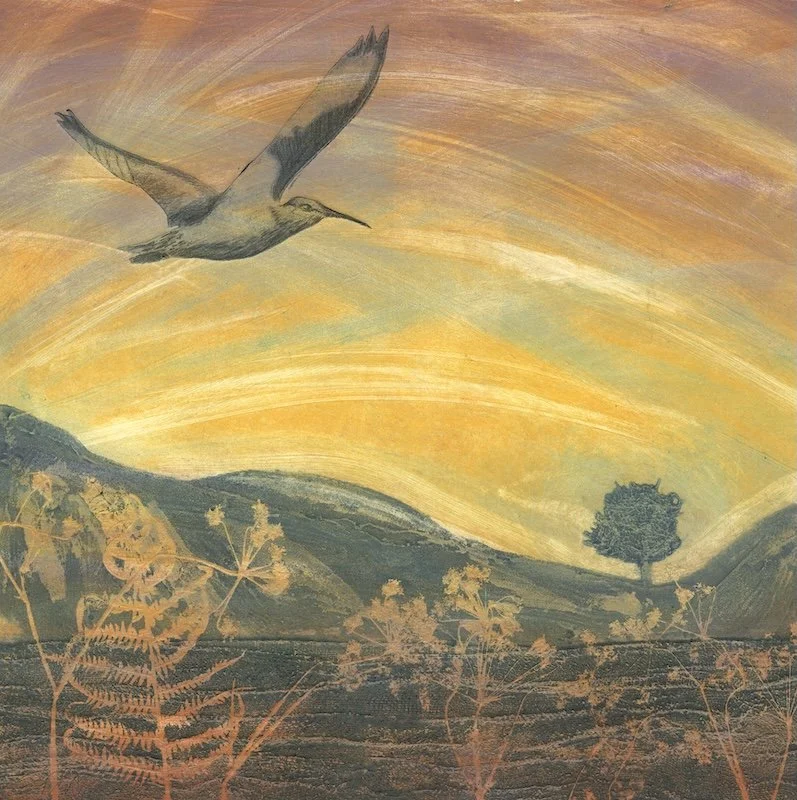

Coming Home - a monotype/collagraph print using a base plate plus a smaller shaped plate for the curlew, a plant material as a mask to allow the monotype colours to come through in the foreground.

Combined Technique Prints

Several years ago, I began to explore the idea of combining both techniques, and through those experiments, I began to produce work that was richer and with more depth. Most of the time I print the monotype layers first and then finish off with the collagraph plate. I’ve done it this way in order to preserve the rich texture of the surface that a collagraph adds. That said, I’m a rule breaker, even my own rules, so I am willing to try printing the collagraph base first, then adding the monotype layers on top to see what happens. Such layering creates complexity and depth impossible with either technique alone.

Each of these combined works is unique because the monotype element dominates, but even without the monotype element, I change the collagraph every time I print through a change of palette and/or the addition of other elements, such as the use of a shaped plate or found materials.

Original Prints vs. Mechanical Reproductions

Now, let's contrast original printmaking with mechanical reproduction.

Mechanically mass-produced prints are reproductions of artwork created in another medium. Someone photographs a painting, for instance, and prints that photograph using commercial printing equipment—offset lithography, digital printing, whatever produces the desired result most efficiently.

These reproductions serve a valuable purpose: they make art accessible and affordable to those who can’t afford original art. There's nothing wrong with owning a beautiful poster of a favourite painting. But it's fundamentally different from an original print.

The key differences:

No artist-made matrix: There's no plate, stone, or screen created by the artist's hand

Reproductive intent: The goal is to copy something that exists elsewhere, not to create something new

Often unlimited: Mass-produced prints may have no edition limit, known as an open edition.

Indirect relationship to the artist: The artist may have no involvement in the reproduction process

To identify an original print look for the plate indent at the edge of the image

A giclée print will have no indent because it is produced digitally.

Where Do Giclée Prints Fit?

This brings us to the fine art giclée prints I sell on my website. These occupy an interesting and sometime controversial middle ground.

Giclée (pronounced "zhee-clay") is a term for high-quality inkjet printing using archival pigment inks on fine art papers. When I create giclée prints of my work, I'm photographing or scanning an original monotype or collagraph, with careful colour-correction, and printing it using sophisticated digital equipment.

Are these original prints? No, they are not—they're reproductions, and I'm quite transparent about that. I created the original using printmaking techniques, but the giclée is a photographic or digital reproduction of that original, and printed digitally in small editions of 20.

Giclée prints are produced with more care and attention to the quality than mass-produced prints—using archival materials, careful colour management, and limited editions. Giclées can be high-quality collectables in their own right. They're not the same as the originals, but they're not mass-market posters either.

I'll explore the relationship between original prints and giclées more deeply in [Original Prints vs. Giclée: What Should You Collect?], but the crucial point is understanding the distinction: giclées are reproductions, even when they're beautiful, archival, and limited.

Traditional Techniques in a Digital Age

We're living in a fascinating moment for printmaking. Digital tools have revolutionised image-making, and many artists incorporate digital processes into their work. This raises questions about boundaries and definitions.

If an artist creates an entire composition on a computer and prints it using archival inkjet technology, is that an "original print"? What if they combine hand-drawn elements with digital manipulation? These questions don't have universally agreed-upon answers, and I'll explore this debate more thoroughly in [What Makes a Print Valuable?].

As someone working in traditional techniques—physically building plates, mixing inks, pulling prints through a press—I love the whole tactile process and the particular qualities these processes create. The embossed texture of a collagraph, the luminous way monotype inks sit on paper, the slight variations between impressions—these can't be digitally replicated.

While I believe maintaining distinctions helps everyone—artists and collectors alike—I’m not against the idea of digitally created prints that are conceived by an artist who is using the same exploratory approach to push the creative boundaries of the technology, as long as everyone understands what the artist is creating and what the collector is acquiring.

Why It Matters

Understanding what constitutes an original print matters for several reasons:

Value and pricing: Original prints typically command higher prices than reproductions, reflecting the artist's direct involvement, the skill and time required, and greater scarcity.

Collecting decisions: Knowing whether you're buying an original artwork or a reproduction helps you make informed choices about where to invest your budget.

Appreciation: Understanding the process deepens your appreciation of the work. When you see the embossed texture in one of my collagraphs, you're seeing evidence of pressure, of materials, of process—a physical record of making.

Supporting artists: Buying original prints directly supports artists' practices in ways that mass-produced reproductions may not.

Next Steps in Understanding Print Collecting

Now that you understand what original prints are and how they differ from reproductions, you're ready to dive deeper into the world of print collecting.

In the next post in this series, [Understanding Print Editions: Limited, Variable & Open], I'll explain what those numbers on prints mean (like "5/25"), what different edition structures signify, and why edition size matters to collectors. If you have any questions, feel free to ask, and I will do my best to answer them.